I'm sure you're more than well-aware that Danganronpa is not an English-made game. The only reason Western players get to enjoy Danganronpa officially is through the efforts of NISA (Nippon Ichi Software America). However, there comes a slight issue with this...NISA is not known for the highest-quality of work. As such, there are hundreds of mistranslations in the English Danganronpa series, ranging from understandable mistakes to WTF? moments. I feel it's important to bring to light these mistranslations, as many are the root cause of popular complaints and misunderstandings. Danganronpa may not be a world-class masterpiece of work even in the original language, but the countless errors in the official NISA translation does a massive disservice to many moments in the franchise.

WHY SHOULD I TRUST YOUR WORD?

Honestly? You don't have to - I'm not even asking you to! I understand feeling skeptical. I'm one person with a website, and NISA is a whole company. How could I know better than them?

The fact is: translation doesn't work like that. A lot of NISA's translations suffer from being too literal, at the cost of misrepresenting the meaning of the text. Does this mean NISA's translation is inherently wrong? No, not really. It's wrong in some aspects, but not all of them. Translation isn't like math: there's no one correct answer. A single sentence in Japanese can be worded a million different ways in English. For example, would you say there's any difference between these three sentences?

- "I don't have time for that."

- "I do not have time for that."

- "I ain't got time for that."

Some of you reading will tell me only the 3rd sentence is meaningfully different from 1 and 2. Some will say they all mean the same thing, so who cares? Some will say that the subtle difference between 1 and 2 can say a lot about someone's personality. Maybe it even depends on context. So, in the end...which is right, when the original language you're translating from doesn't even work remotely similar to the one you're translating it into?

That is the ultimate hardship of translation. No matter how fluent you are in either English or Japanese, translation itself is its own skill. As such, I do not blame NISA's translators for the many mistakes in the Danganronpa games. Often times, it is not the translators fault, but rather, a result of higher-ups pushing time-constraints, meddling, and a fractured work environment with minimal communication between parties.

So, Why should you trust me? You shouldn't. I don't want you to take my word as gospel, nor assume I myself will never make a mistake. But what I aim to do is provide as much information as possible, show you my own work from start-to-finish, so you can understand each component of the Japanese sentence, and follow my thought process to how I reached my conclusion. From there, you can decide for yourself how you feel.

Remember what I said: translation is not math. There is no one right answer. Just dozens of similar - but different - solutions.

Below are some starter articles. I recommend reading them if you are unfamiliar with Japanese. Don't worry - I promise they're interesting! (Also...pretty integral to understanding the rest of this page).

FOR STARTERS - LITERAL VS. EMOTIONAL MEANING +

I think a lot of people get confused when trying to grasp the idea of a "literal" translation versus an "emotional" translation. The easiest, to-the-point example to help you understand is this simple question:

How would you translate the phrase, "You can't have your cake and eat it too"?

If you just thought, "I'll just write it in the language I'm translating it into", congrats: that's the literal translation.

If you just thought, "I'll re-write the sentence into what the phrase conveys ("two things can't be true at once") and translate that", congrants: that's the emotional translation.

Because, most likely, the other language doesn't have that idiom. So, when say, Japanese players, read the line, "You can't have your cake and eat it too", they won't think "Right, both things can't occur." - they'll think, "Huh? Why are we talking about cake?"

But, what if the exchange goes something like this?

A: You can't have your cake and eat it too.

B: Yes, I can! I'll have my cake, then I'll eat it!

In English, this is a funny argument between two characters, where B's reply serves as both a joke and a point: poking fun at the ridiculous wording of the idiom, while also showing the audience that they're rebelling against A's actual point that they can't have two things at once. I'm sure you can think of many movies or shows with a similar scene.

But now, back to translating: how do we handle it?

Because, now, this scene hinges on both the literal and emotional context of the phrase. If we go full literal, the Japanese audience will still be confused as to why cake was brought up in the first place at all. But if we go full emotional, we miss out on the humorous beat that English viewers would have laughed at; as it stands, Japanese viewers would just view it as a tense argument (which could feel totally out of place, since this scene is supposed to be somewhat funny!).

There are many ways to handle this, but usually, it falls into one of three categories:

- The "Have Your Cake and Eat It Too" Method

- Localization Method

- T/N Explanation Method

Let's look at each one, and decide which we should go with.

The "Have Your Cake and Eat It Too" Method

Named after the point of this very phrase, this translation method is a sort of "brute force" one: just try and combine both meanings as well as you can.

An example may look like:

A: You can't have your cake and eat it too. One of those things has to go.

B: Yes, I can! I can have a cake, and then I can eat the cake! Just like what I'm going to do now!

With this method, the audience is taught what the phrase means retroactively, now being able to grasp both the literal and emotional meaning of the scene. They can laugh because arguing about cake sounds ridiculous, but still go, "Yeah, I see both A and B's point."

Now, there's many upsides and downsides to this method as with all translation: it's very hard to pull off in a natural-sounding way. A lot of the time, it can come off as "explaining the joke", which often kills any humor the joke held in the first place. Furthermore, it can still sound confusing if not clear enough. The point of why you're laughing also changes: where in the original, viewers were laughing because they were already familiar with the phrase, thus found the counter-argument amusing, our new audience is simply laughing at the fact that it sounds ridiculous; they have no prior attachment nor knowledge of this phrase since they just heard it for the first time.

You might think, "So, what? They're laughing at the same part English viewers were laughing at. Who care why they're laughing?"

And many would agree with you. Many would also disagree and say it's more important to match the "why" instead of the "how".

If you're one of the ones who disagree, let's take a look at the second method.

Localization Method

Some anime/game/manga fans hear the word "localization" and shudder, but I promise that good localization is nothing to fear. The localization that gets mocked the most is the excessive kind, where they change onigiri to jelly donuts, despite the fact it's unnecessary and clearly not what is being shown on screen.

A good localization knows what they're changing and, most importantly, why they're changing it. For example: Phoenix Wright, and all the other characters of his series, having their names changed to be puns in English only works as well as it does because they were already puns in the Japanese version - puns that would make no sense to English players. Thus, a localization was in order: give them new English names that suit the original joke.

Therefore, to localize this exchange, we have to identify the purpose first and foremost, as well as why we have to change it.

The purpose of the scene is:

- Supposed to make the viewer laugh, specifically by making witty commentary on something we all agree about (most people think the phrase "can't have your cake and eat it too" is nonsensical and untrue) - put more simply, take something the viewer is already culturally aware of and poke fun at it.

- Supposed to show B is rebelling against A's point; this is still an argument, and B is disagreeing emphatically.

- The point in question, specifically, is that B is trying to have two things their way.

As for why it must be changed:

- Japanese viewers don't have the literal phrase, "eat your cake and have it too" in their language. Keeping it literal would be confusing and distract from the purpose of the scene.

Now, this is where the trickiness begins. There are hundreds of ways we can then go about this. And, bluntly speaking, being able to come up with something that will be a perfect translation will likely be impossible. Our final version, for example, is not going to be literal no matter how hard we try: keeping the cake metaphor just isn't gonna cut it. (badum-tiss...)

This is why we broke it down to essential points: what information is being conveyed, and why the joke is funny.

Now, lucky for us, Japanese does have a somewhat similar phrase with somewhat similar grievances. It's not exact, and therefore not perfect; where the English phrase specifically is meant to emphasizes "you can't have both at once", the Japanese version emphasizes "focus on one thing at a time", which are just different enough that people have debates on weather or not these two phrases are comparable.

The phrase in question is 二兎を追う者は一兎をも得ず - "One who chases after two hares catches neither."

The grievance that arises from this phrase, though, is not so much the wording, but the message itself: there are nitpicks that it is demoralizing, nonsensical, and that "only the one who chases two hares will end up catching two". This makes the phrase feel closer to "jack of all trades" - another English phrase many English-speakers feel is demoralizing, and thus follow up with, "is still better than a master of none."

Because of these minute differences, the scene can't progress in the exact same way as before, but we can get pretty darn close.

A: Those who chase two hares catch neither.

B: But only the one who does chase two has a chance at catching both!

There's a number of alternative versions we can go with, too. There's no real set "final phrase" to this saying - more or less, just various rebuttals that are similar in phrasing. A common one in recent times is, "Why not chase two hares?"

Personally, Localization is my go-to with translating. Obviously, it depends on context and what ends up working the best for the type of media, but to me, the only reason we bother to translate at all is so another culture can enjoy a work. If you don't make that work have the same impact on that new audience, then it doesn't really feel like you're translating the emotions along with the words.

This is not to say Localization is the perfect method. In some cases, literal translations are more needed, or perhaps, later scenes/imagery can cause localization to not work as well.

For example, substituting the hare saying works as long as this conversation remains just that: a conversation. But what if actual cake is involved? Or there is some on-screen visual referencing cake? In this case, our Localization - though pretty good on paper - will just be more confusing in practice.

Especially if our work is heavily intertwined with the culture it takes place in, changing things can have huge ramifications. A story that takes place in Edo Japan will rely heavily on that fact, for example, and so we would have to very carefully weigh the pros and cons of how to translate certain aspects.

T/N Explanation Method

I'm gonna be honest, this is my least favorite form of translation. It works fine for blog posts and websites, but for officially released manga, games, and anime, I feel that it only serves to suck the viewer out of the experience. You might feel differently however, and that's okay. All these methods have a place.

Put simply, this method is the famous "keikaku means plan" situation. Where, if you simply can't think of anything, just explain in your own words what's happening in the scene as an aside note (typically referred to as a TN or T/N - "Translator's note")

A: You can't have your cake and eat it too.

B: Yes, I can! I'll have my cake, then I'll eat it!

T/N: "You can't have your cake and eat it too" is a common English phrase used to mean "You can't have both things at once". This phrase is often criticized for linguistically making little sense.

I really don't want to rag on this translation method, because it has its place. I, personally, use it as a last resort if I absolutely cannot think of anything else. Again, I think it is perfectly fine in a blog post or a detailed website like this, but in a published work (physical manga, anime episode, video game) it feels very jarring and out of place.

Final Thoughts

So, what do you think we should go with? We've presented three translation methods, and one example for each. This is the hardest part, because there's nobody to tell you if you're right or wrong, as all methods are technically correct in their own ways.

I hope now you have a better understanding of the translation meta. Even if you know two languages perfectly, it can still be really tricky! So, if you're a translator, give yourself some grace, as well as your fellow translators. This page was not made to mock NISA's efforts, but to offer my own view out of love for Danganronpa.

FOR STARTERS - FOCUSING TOO MUCH ON THE LITERAL +

Last article, we talked about the difference between literal and emotional meaning. But...what exactly is literal meaning? Last time, we approached it more from a theoretical point-of-view, as I asked you to consider how you would go about hypothetically translating an English phrase. I think it's about time we use some actual Japanese-to-English as a hands-on example.

But, before we look at the example, real quick: let's talk about what "literal meaning" refers to precisely.

In short: when I talk about "literal translation", I refer to two main points:

- Emphasizing, or downright exclusively focusing on, the literal text and not the "meaning" of the words. (e.g. finding it more important to keep the word "cake" than the meaning "you can't have two things at the same time")

- How these words are "defined" as per dictionaries.

Obviously, with English and Japanese being totally separate languages developed apart from each other, the only way a "literal" translation could exist is if somebody has declared that there does exist a 1:1 translation for every given word. While there's no singular person to "blame", the "authority" on this matter are JP to ENG dictionaries.

These dictionaries are incredibly useful as springboards and for beginners, but should never, EVER be used as an end-all-be-all. They are useful guides to get your feet on the ground, and that is it. With two languages so different, very few words have an actual "translation" that a dictionary could just tell you about. Yet, Danganronpa falls victim to very obviously using whatever the English dictionary says a Japanese word should mean, when the meaning often changes with context, and that a dictionary can't impart the same nuance as live examples can.

I find that, often, looking up a Japanese word in the Japanese dictionary will give more accurate results than looking it up in a JP to ENG dictionary. But just like with English dictionaries, sometimes you don't grasp the meaning of the word until you see it used in several example sentences.

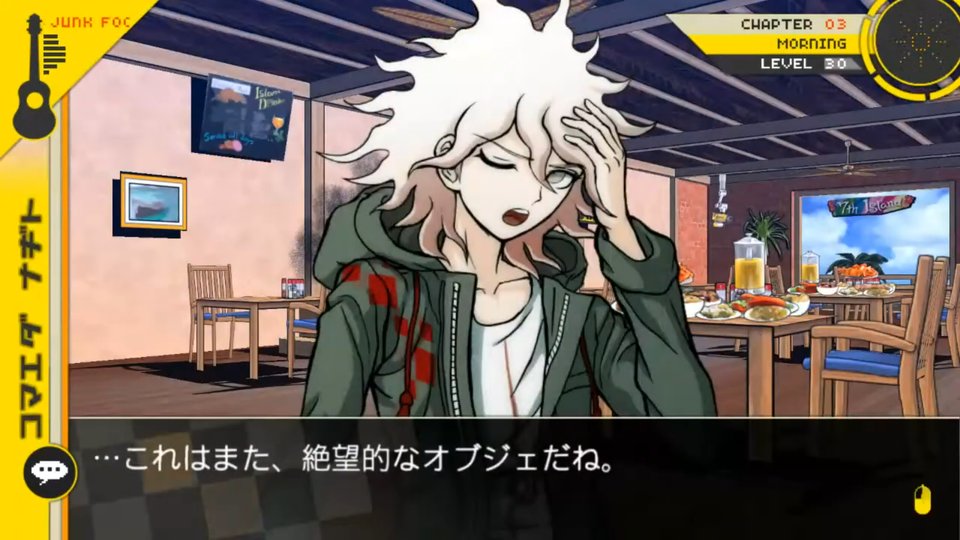

With that context, let's dissect this translation:

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

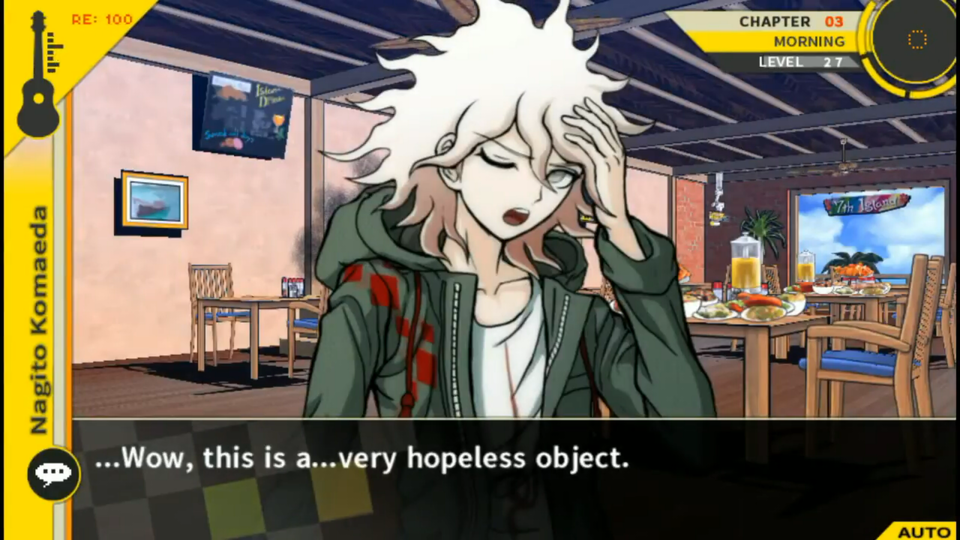

| Official Japanese (Screenshot source: baja) | Official English (Screenshot source: Hikkie) |

Our first sentence is a simple one, yet with many fumbles in nuance on the English side. I will list the three words of contention, written in Japanese, Romanji, and how they are translated in the Official English shown above:

- また - Mata - "Wow"

- 絶望的な - Zetsubou-teki-na - "Hopeless"

- オブジェ - Obujee - "Object"

Let's start with また.

As it stands, I think the translator read これはまた as これまた, a phrase of exclamation (making it, lit: "This is really [awesome/horrible/etc.]"). While definitely not impossible given this scene, consider the context: right before Komaeda began speaking, Tanaka had just exclaimed about how dreadful this display was. That, combined with the fact that the phrase Komaeda is using has は in it (whereas the exclamation, typically, does not have the は particle to separate the two words) leads me to believe that the また in this sentence is supposed to be read not as an exclamation, but as an addition, as it is commonly used, making it:

| Also, this is...

Why did the translator not catch this, then? Well...I can't say for sure, but my suspicion is that the translation for Danganronpa was done out of order, meaning lines were translated independently of the context they were spoken in. There are several lines of dialogue which give me this feeling (which we will discuss in later articles), and if true, explains a lot. Japanese, more than many other languages, is very context dependent. Without the context of the scene and surrounding dialogue, mistakes like this are easy to make.

That's just a theory, of course. Through all my research, I have found very little in the way of statements from the English translation team. All I have are educated guesses drawn from the work shown to me.

Next, let's focus on the words that were translated too literally.

If you look up 絶望的 in a JP to ENG dictionary - like Jisho.org - you'll get one definition:

| desperate; hopeless

If that's true, why not call it a "hopeless object"?

Well...what does a Japanese dictionary have to say about it?

Kotobank.jp says the following:

| まったく希望がもてないほど悪くなっているさま。

| A state when things are so bad that there is absolutely no room for hope.

What catches my attention in this definition is the critical hinging factor: "when things are so bad that..."

Another site, kimini.online, curiously claims there to be a difference between the word "Hopeless" and "Desperate":

| hopelessも希望がない、desperateも絶望的でありとても似た表現です。

| "Hopeless" is when hope does not exist. "Desperate" is when there is no room for hope, making both very similar expressions.

Literally speaking, 絶望的 means "point void of hope". It's hard to translate the above passage in a way that would be literal yet still readable in English, but to be as specific as I can: hopeless (希望がない) is when hope does not exist. Desperate (絶望的) is when a situation or quality is void of hope.

They then go on to show different sentences where the two words are, in fact, not the same. It's an interesting read that I recommend checking out.

In their own article, they define 絶望的 as:

| very serious or bad.

Again leading us back to this definition hinging on things being bad, more so than being "hopeless". Or, more accurately, that things are hopeless as a consequence of things being bad.

Considering this, I feel both 絶望 - and by extension, 絶望的 - are closer in meaning to the English word "misery", for being centered more on the negative feelings where the lack of hope is the afterthought. The way it is used in Japanese often aligns itself with this English word.

Now, of course, context can change the meaning of the word, and in some cases, "desperate" or "beyond hope" do work better. Every word is flexible to some degree, and to assign one English meaning to a Japanese word (and vice versa) would land us back in the same situation we were stuck in before.

But, for this specific instance of how Komaeda is using it, I do believe "miserable" makes more sense.

Okay, so what about オブジェ?

If you're familiar with Japanese, you'll know that there are several "loan words" - words that are taken from another language and used as-is. These words are usually written in Katakana. For example, コーヒー ➔ koohii➔is "coffee". What's wrong with オブジェ, then? It's clearly supposed to be "Object".

Well...another issue that arises is the fact that just because a word is based off an existing English word, that doesn't mean it'll have the exact same meaning. I think a similar example that can be used is how "fries" and "chips" refer to the same item but in two different dialects, but in American English, "chips" are a completely different food item, which can cause confusion.

Furthermore, there's a good chance it doesn't even mean the English word for object at all - rather, it means objet, the French version of "object". "Objet" has a slightly different meaning than the English word "object", and this French meaning lines up pretty well with the Japanese version.

Before I reveal that, here's a fun little at-home experiment you can do: type "object" into any browser search, and then look at the images. Then, do the same, but type オブジェ. You'll notice the results you get are pretty different, and therein lies the reason why this word can't simply be translated as "object" as it is used here: it refers to art!

Komaeda is specifically calling what he sees not some mere object, but an art piece. We can use any number of terms that fit this definition, but I'll personally go with "display", since it captures the artsy connotation while still being vague in the same way objet is.

Finally, putting it together, we can correct the first sentence to be:

| Also, this is just a miserable display.

Where before, Komaeda's words sounded unnatural and confusing (what does it even mean for an object to be hopeless?) now it sounds like he's giving the critical comment that he was in the original.

And if you're wondering where the word "just" comes from - it's how I'm choosing to naturalize ね in this sentence. ね as a particle is meant to be conversational. Sort of a very light, unspoken, "You get it, right?" - that's the best way I can put it, at least. "Just" is used formally as a quantifier ("just enough") but casually, it's often inserted for emphasis to draw attention to the main point, which Komaeda is doing here: he's rounding out Tanaka's criticism of the horrific art piece by adding on the fact it's, at its core, miserable.

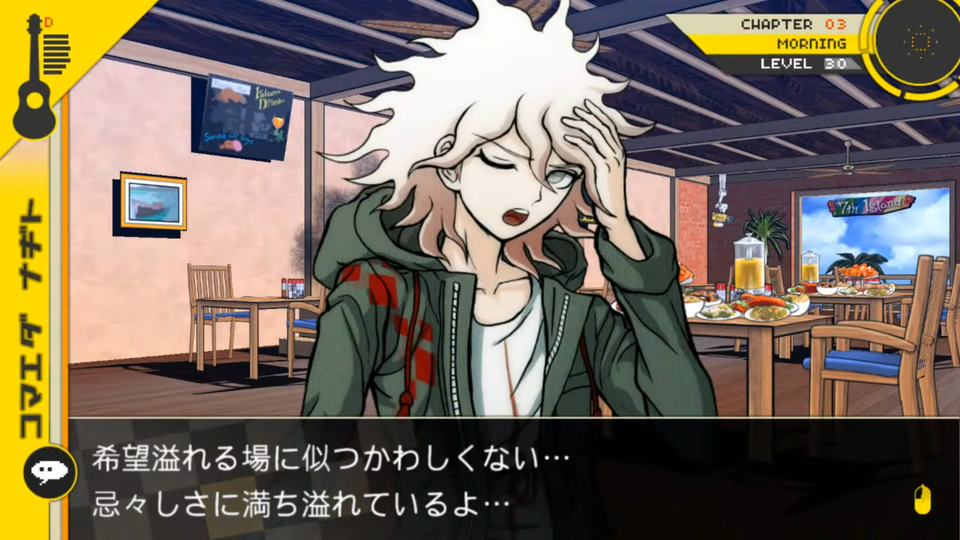

Now, let's check out the next section.

- 希望 - Kibou - "Hope(ful)"

- 溢れる - Afureru - "~ful (in "Hopeful")"

- 場 - Ba - "Place"

- 忌々しさ - Imaimashi-sa - "Malice"

- 満ち溢れる - Michi-afureru - "Brimming"

The first part of this sentence contains an error in nuance when it comes to the Official English, and it lies in this word: 溢れる. This word is used twice in this scene, which makes it a fantastic example as it is used to different effect in both sentences.

A JP to ENG dictionary will define 溢れる as "overflow", and this is mostly sound; the image it is supposed to invoke is that something or someones (an abstract or tangible concept) is spilling out or about to spill out from its containment (a cup, a venue, etc.).

The issue comes with confusing this "to be full [of]" with being [something]-ful.

Something - in this case, brimming with or containing a lot of hope - means just that: the hope is flowing out from, or residing inside, of something - not that this appointed something itself is hope - which is what the English word "hopeful" would imply.

This is why we get the first error in our sentence: this place is not "hopeful" - this would imply the "place" itself has a hopeful quality, which Komaeda outright denies in his second FTE, where he says, rather, "Hope exists on this very island."

Komaeda in this sentence is actually saying:

| This is a place brimming with hope; it doesn't belong here.

This is a little more vague in the same way the Japanese version is. It can sound like his usual nonsense at a glance, but it's very important with a nuanced character like Komaeda to keep his worldview straight: the question we may find ourselves asking with this tweak is "why does he think this place is brimming with hope? What makes it that way?" and, whether now or later, we can conclude that it's because of the people currently on this island - the Ultimates - that make it a place "brimming with hope".

Now, the second sentence in this scene runs into a similar issue: remember how I said that Komaeda uses this word twice? Well, here, we see it again in the form of 満ち溢れている. This word can seem incredibly similar, as it is also defined as meaning "overflow" - but, whereas 溢れる means to be "brimming with" or "spilling over" - like a cup of water you poured just a wee too much into - 満ち溢れる means bursting forth, like a dam breaking under the pressure of a deluge. This word is also used to mean being overwhelmed or overcome with, like with rage or joy.

These two words - 溢れる and 満ち溢れる - can oftentimes be interchangeable, hence the confusion, but there is still a difference, and in written works of fiction, I think it's important to always consider the intention behind each word chosen.

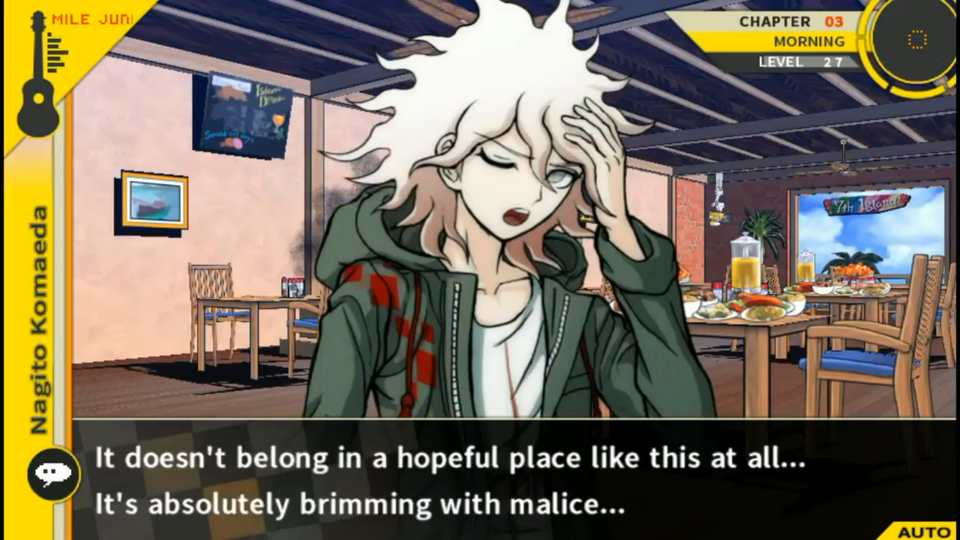

満ち溢れる also tends to be the more metaphorical of the two, though both can be used in a metaphorical or literal sense. We see that common metaphorical usage here, however, with Komaeda's second sentence: which is where we also run into our next issue.

Beyond the semantic issues, there lies a mistranslation here, with an easy explanation as to why it occurs. The word 忌々しい (base adjective of 忌々しさ) is often confused with 忌まわしい due to some sources erroneously listing them as synonyms; considering they share the same Kanji and similar root meaning, it's understandable to see how.

But 忌まわしい is the one that means "malice; foreboding; evil; morally reprehensible" ...you get the picture.

On the other hand, 忌々しい means to be downright infuriating. Pisses you off and drives you up a wall.

Both words have 忌 as the Kanji, which its base word, 忌む, means both "shun" and "detest". 忌まわしい captures more of the "shun" aspect while 忌々しい is "detest".

This word is also much more subjective-sounding than 忌まわしい, since it is describing feelings of anger rather than a level of being deplorable (which is usually leveled at things like wars or disease, which can be readily agreed to be deplorable).

Not that 忌まわしい isn't also subjectively used, but of the two, 忌々しい is certainly more subjective.

Because of this, we can infer that Komaeda is speaking from his own perspective, and he is REALLY upset, as compounded with 満ち溢れる - our more "emotional" word, as described, that means to be bursting with.

This line better reads, then, as:

| It's downright pissing me off. (Lit: [I am] overflowing with extreme anger.)

So, all together, Komaeda is saying in these screenshots (with some English connectors to sound more natural):

| Also, this is just a miserable display.

| This is a place brimming with hope; it doesn't belong here, and it's downright pissing me off.

Maybe you're reading this and thinking, "Eh, it's not really that different from the NISA version." in which case...the rest of these articles will probably bore you xD (well, save a few egregious exceptions...) because I find that the mistranslations in Danganronpa is more of a "death by 1,000 paper cuts" sort of situation. So many minor nuances are taken away to the point that we are left with almost entirely different characters.

Now, if you read this revised line and thought, "Holy shit, that's a totally different sentence/impression," then, oh man, do we have a lot more to tackle together.

I hope now you can better understand both the effect of hyper-literal translation as well as my own thought process in researching and reconstructing these scenes from the ground up. Remember: I'm not here to blame NISA's staff. There is only one translator listed for the English credits of SDR2 and DR1. Things like these can waver in size, but for a text-heavy game in 2014, produced by a moderately sized company like Spike Chunsoft and NISA for a franchise that did incredibly well in Japan, one translator and time constraints is a horrible decision, and I do not envy the position they were put in.

I had the leisure of writing this article over the span of a few days between work and hobbies, to cross-reference different parts of the game, to do research, and to mull over my own thoughts on how I wanted to convey the topic in English. Time that the official team was obviously not allotted.

Oh, and one more thing. When I do these re-translations and all is said and done, I like to go back in time and check how orenronen - the creator of the Let's Play Danganronpa threads on SomethingAwful back before the Official Translation was made - translated these scenes, since I believe in cross-checking work and learning from others.

Looks like we had pretty similar ideas! xD

This page is under construction! Thank you for your patience.